Only 7.5% of Lok Sabha MPs are credited for asking 50% of starred questions and 13% of MPs are credited for 80% of all questions! [2]

Since June 2015 I have been working as a legislative assistant in the office of Mr P D Rai, the Lok Sabha MP from Sikkim. It has been a really interesting experience and the work is diverse and engaging. The only component of my work that I’ve always been critical of is preparing parliamentary questions.

During my training period for the job, parliamentary questions were presented to me as an excellent tool that MPs can use to keep the government accountable. These questions provide MPs an opportunity to get information from all ministries and evaluate their functioning. Though there have been several parliamentary questions that have brought out useful information from the government, the effectiveness of most questions is far from ideal. I’ve talked to a lot of people working in the offices of different MPs across party lines and each one has expressed dissatisfaction at the question selection system in Parliament.

Some MPs get much more than their fair share of questions while others struggle to get even a single starred question in the list.

Just last week, on 10 March, Jithender Reddy a TRS MP from Telangana expressed how bad the questions system is.

How it works

Each MP can submit a maximum of 10 questions for each day of the Parliament’s sitting when question hour is to take place. The submissions are made 15 days before the date assigned for answer and a paper signed by the MP listing the question must be submitted in the parliamentary notice office.

Out of that, a maximum of five questions will get picked for answering. There can only be 20 starred questions, which are due for oral answer and 230 unstarred questions, where written answers are provided, on each day. Every MP wants a starred question, that too in the first five of the list, as these are the only ones which will be answered on the floor of the House and where MPs can ask supplementary questions. The rest only get written replies, which might not be very satisfactory.

Looking at questions day after day gives one the distinct feeling that something in the system is not right…

The biggest problem with the questions system is the fact that more questions are submitted than can be answered, so which question gets picked is decided by a ballot process, which is basically a lottery. It’s always felt ridiculous to think that important matters in our Parliament are decided based on a lottery, but what’s worse is that looking at questions day after day gives one the distinct feeling that something in the system is not right, and some MPs get much more than their fair share of questions while others struggle to get even a single starred question in the list.

Why so many questions?

At the outset it seems like an MP who puts in more questions or participates in more debates is a better MP as he or she is more involved in parliamentary work. Organizations like PRS Legislative Research also list MPs in order of attendance, number of questions asked, debates participated in etc. But what one realizes after viewing Lok Sabha TV day in and day out is just how pointless some of the questions are. MPs have been putting in questions solely for the sake of growing their ranking in the list, and the entire question system designed for keeping the government accountable has turned into some sort of a game, where the only thing that matters is numbers.

MPs have been putting in questions solely for the sake of growing their ranking in the list, and the question system… has turned into some sort of a game.

How do we know something’s wrong?

Since I joined office, I’ve been thinking about trying to figure out how some MPs get most of their questions selected while others get less than a third. While discussing the question selection process in my office, we decided to start analyzing the data. We found some really interesting statistics that show how some people have figured out loopholes in the Parliament’s system of selecting questions and used that to get most of their questions listed.The 16th Lok Sabha that came into existence after the general election results in May 2014 has had 122 days of questions being answered until 3 March 2016. This means that the maximum number of questions that could have been selected for any MP is 122 X 5, which is 610 questions.

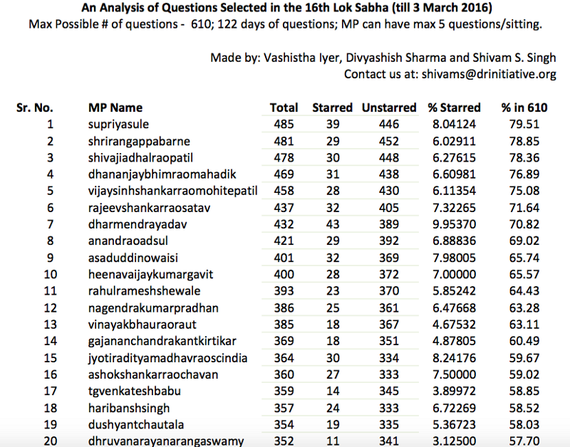

Below is a list of the Top 20 MPs who had the most number of questions selected.

The top few MPs have a selection rate above 75%, while my MP’s office which submits the maximum permissible number of questions every day (other than a maximum of four days that we miss every session) has a selection rate of 45.4%, which puts us at a very respectable 80th position, but far from the top. The story is similar across a lot of MPs offices who’ve put in the maximum permissible limit of questions and have a selection rate of around 50%.

After adding the MPs’ states and political parties, we found that eight MPs out of the top 10 and 12 out of the top 20 are from Maharashtra.

At first glance itself, something in the list doesn’t seem right. After adding the MPs’ states and political parties, we found that eight MPs out of the top 10 and 12 out of the top 20 are from Maharashtra.

How can this happen?

We talked to people from the offices of many MPs to get an idea of how many questions their office submits to Parliament. The actual figures of the number of questions submitted are not publicly available and only the selected questions are listed by the Lok Sabha. These conversations gave us a fair idea that most offices we contacted submit the maximum allowable number. This led us to wonder whether something is wrong in the question selection process.

We analyzed the percentage of starred questions to the total number of questions for each MP, because if someone could influence the question selection process they would definitely want their question to show up as a starred one. This analysis told us that though there was variation in the percentage of starred questions selected for MPs, it was nothing out of the ordinary. We were not able to find any evidence of tampering from the side of the Lok Sabha secretariat. Yet some MPs were getting almost twice the average number of questions…

The Answer

The Lok Sabha secretariat clubs similar questions from different MPs together before conducting the ballot and lists all their names as the asker of the question. This provided us the answer to how an MP can have so many more questions admitted.

[T]here are two sets of MPs, mostly from Maharashtra, who ask the same questions at the same time.

The MPs with the columns highlighted in red had more than 90% of their questions clubbed with other questions. The average for MPs who had more than 20 questions is 68.83% of the questions clubbed with a standard deviation of 13.226. This means that there is less than a 6% chance that any MP had over 90% of the questions clubbed. Factoring in the fact that there are multiple MPs with more than 90% clubbed questions, most of whom are from Maharashtra, the probability of this happening by random chance goes to almost zero. The ones in green are MPs who had a high question selection rate without having a high proportion of clubbed questions.

This reveals that there are two sets of MPs, mostly from Maharashtra, who ask the same questions at the same time. The surprising fact was that the first group includes MPs from NCP, BJP and Congress while the second group of Maharashtra Shiv Sena MPs also has Dharmendra Yadav, a Samajwadi Party MP from UP in the mix.

It was good to know that there were at least a few MPs in the top 20 list who had unique questions and yet were able to get a high level of questions in.

Why this is a problem

This is an excellent example of cross-party collaboration amongst MPs and would have been great for our democracy if it extended to other areas of Parliament as well.But what this data shows is that the question system in its current form does not offer an equitable opportunity for all MPs to hold the government accountable.

The data shows that the question system in its current form does not offer an equitable opportunity for all MPs to hold the government accountable.

This leads us to the question that whether this purely quantitative approach is the most suitable for our Parliament.

The proposed solution

The questions process in Parliament must be reformed to make questions serve their true purpose of keeping the government accountable. Here are a few reforms that would help make parliamentary questions more relevant.

- Reduce the number of questions each MP can ask so that they only raise relevant questions instead of trying to boost their question-asking statistics. This would also allow for all questions to be answered by the ministries instead of holding a lottery to decide what’s answered.

- Stop maintaining a list of questions with the MPs’ names. Only the questions should be listed, not who asked them. This would also allow for MPs to ask more relevant questions that they truly want answers to. The questions wouldn’t contribute to their statistics or hamper their relations with any party that the question might adversely affect.

- Every MP should be given priority to ask at least one starred question that will be orally answered on a rotational basis. The ballot can decide on which MPs ask the question in which order.

- A platform should be created where MPs and citizens can post questions and then citizens can upvote those questions. The questions with a certain number of upvotes should be taken up on a priority basis and compulsorily answered.

- The platform can be extended to debates i.e. Parliament takes up debates on any topic that is upvoted by a certain threshold of people. This keeps the government directly accountable to the people, which was always the true purpose of these tools.

Analysis done by Vashistha Iyer, Divyashish Sharma and Shivam S. Singh

Notes

[1] Data scraped from Lok Sabha website.

[2] For starred questions, a maximum of two MPs are credited; there’s no such limit for unstarred questions. For number of starred/unstarred questions for MPs, data is taken for both clubbed and unclubbed questions combined. Total number of questions used is for unique questions.

[3] The count of clubbed questions shows a different number of clubbed questions from MPs in the different tables. For example, Supriya Sule’s table has 49 questions clubbed with Heena VijayKumar Gavit, while Gavit’s table shows 58 questions clubbed with Sule. This is because the tables are based on the primary asker – the first MP who is listed for the question. Where Supriya Sule was the primary asker, Gavit was also listed in 49 questions.